Loving Orlando was easy.

The hard part was continuing to love when he succumbed to end-stage alcoholism. When our marriage failed I could have spent my life carrying shame and anger. But suffering was a great teacher; meditation taught me how to get out of my head and into my heart.

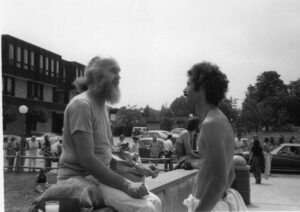

We met in junior high in the suburbs of Chicago. We were twelve years old and it was the big Eighties; mobile phones were the size of car batteries and cassettes were slowly being replaced by CD’s. I was the clarinet nerd in the school band. He was the popular soccer kid that made everyone laugh. At our first dance that fall Aqua Net hairspray hung in the gym like a mist. We shuffled in the dark while Cyndi Lauper whined through Time After Time. Orlando pulled me into our first hug. He bent his head down and sang in my ear If you’re lost and you look you will find me…time after time.

Time did connect us; for thirty years. Orlando would wrap his long arms around me and it was like the moment a mallet strikes a singing bowl; only a joyful ring and mellow sound rippling away. Everything faded except for the present moment. I used to call him my Buddha. Once I asked him how he could always be so happy and chill.

“Bunches,” he said as he tossed his dark bangs off his forehead, “you just gotta relax and say fuck it.”

Years later I’d learn that the wisdom tradition Yoga describes this as non-attachment to results or vairagya. Be steady in your actions, pay attention to this moment, and let the result be whatever it wants to be.

My philosophy was more like show how much you care by worrying a lot. But Orlando would hug me—or I’d play my clarinet—and I’d get back to just enjoying life.

By the time we were juniors in high school we kept dating on and off. I had moved away from Chicago and was up the north woods of Michigan at Interlochen Arts Academy studying classical clarinet. The pressure of my upcoming conservatory auditions loomed and I turned to meditation to help. I had a few cassette tapes I found in a New Age bookshop. They were pretty cheesy, lots of swooning synthesizers and vocal reverb. But the technique was legit. It guided me in a sequence of awareness; body, breath, mind, and sometimes to the spaces between thoughts. I felt calm and cool after; that same hugging Orlando kinda thing.

I was riding in the last waves of the counter culture revolution of the Sixties which favored Yoga that focused on expanding consciousness. I didn’t know it but I was taking my first steps towards finding Integral Yoga; founded by Sri Swami Satchidananda when during a visit to the states from India his “hippie children” convinced him to stay. By watching my body, breath, and mind I was practicing the branch of Raja Yoga; concentration and meditation. I was learning how to embody that “fuck it” philosophy of Orlando. What Alan Watts called the “Big Realization” that eternity and love only exist in the here and now.

From everything he later told me, I’m pretty sure Orlando was already drinking when we were in high school. He told me about his first drink when he was fourteen and he went to see family in Mexico for the World Cup. I can see him there; it’s so hot that his shirt is soaked. He kicks a soccer ball around with his cousins. Someone brings out a chilled six-pack. At fourteen his hands were so big the can would have looked like a toy. The first sip was shockingly cold. As it mixed with his saliva it became part of him. His cousins were satiated and their attention drifted back to the ball. But for Orlando a thirst had woken up. It was so strong that it never left him. All he had was a desire for more.

In college we began officially dating and a few years later we got married. By that time we had known each other for fourteen years. On New Year’s Eve at the turn into the new millennium we celebrated in our new house in suburban Illinois. We drank champagne, smoked pot, and blasted Prince’s 1999. I was growing out the weekend party phase of my early twenties, but he was still going strong.

I was teaching college music courses, gigging, and studying music therapy. I was still meditating, mostly in my car between rehearsals to calm my always racing anxiety. Most weekends I’d come home from a performance and find him in bed, but the basement littered with pot ash and way too many beer cans for one person.

I’d clean up the mess and go onto the deck. I’d sit on the deck and put my feet on the earth. I’d breathe and follow the sequence of meditation I had learned back in high school. As the waves of my mind slowed I saw his drinking and my fear that I had no idea how to help.

When I began confronting him he just got better at hiding it. And I got better at pretending it wasn’t happening.

Four years into our marriage he got arrested for drunk driving. The illusion of our ideal suburban life was outed as a lie. The legal cost and shame blasted the truth of the basement into the light.

He checked himself into rehab. While he was away I did hatha yoga—physical practice—meditated, and blasted Beethoven on my clarinet. Outside of my yoga practice, music was the only thing that helped me function.

Orlando rallied after rehab. He went to meetings, went back to college, and we started hugging in the kitchen again. Four years passed and it seemed like the thirst was gone. This is how addiction can feel; like life titled slightly sideways. Laughing on movie nights, rocking out to the Gypsy Kings while cooking, spooning in bed.

By this time the postural yoga boom was underway. But the classes I found had loud music, subtle body shaming, were low on racial and religious diversity, and had little connection to spirit beyond a token namaste at the end of class. I felt like I was back in the aerobics boom of the Eighties where women’s empowerment came with a price tag of treating my body as a spandex clad project always in need of fixing.

I did eventually land in a yoga class that blew my mind. The teachers in the Integral Yoga tradition were directly from the cultural revolution of the sixties. They showed me a gentle path of yoga that focused on building a whole lifestyle that develops an easeful body, a peaceful mind, and a useful life. Selfless service and interfaith cooperation are essential components.

When they taught me mantra meditation, it was like someone rang a bell I forgot I was holding.

We were guided through verbal repetition of a mantra; a short phrase in Sanskrit that aids concentration. The syllables Om Shanthi purred in my chest. We eventually dropped chanting and sat in silent repetition. I still felt the mantra vibrating. It held me enough so I could observe myself. I saw that despite my denial Orlando was drinking again—the constant use of Altoid mints, requests for money, the latest lost job that “wasn’t his fault.” I saw my anger and that I wasn’t nearly as loving as I thought.

Mantra meditation felt like the link between the feeling of pure being-ness I had with Orlando and my everyday life. Mantras not only helped me concentrate, they are also a pure capsule of universal energy. By chanting or repeating it the qualities of the mantra are brought forward. Shanthi means peace, but not a fleeting sensation. Rather, it is the essential nature of peace itself. The sound vibration brings us out of the rational mind and into the heart; the full experience of the present moment. Bringing in chanting—even silently—tethered my musical nature with my spirit and gave me a tool that was portable and practical.

Over the next year Orlando began drinking more bravely. He got drunk at my sister’s birthday party and was belligerent and rude; accusing her guests of being selfish and small-minded. He passed out once when I was getting my hair cut and I pretended that he was having low blood sugar. Lying became my regular thing. Shame lay underneath it all.

I also became obsessed with Integral Yoga and soon went to Satchidananda Ashram-Yogaville in rural Virginia. I stayed for a month long immersive yoga teacher training. After the chaos of home, the peaceful nature of the ashram felt like a sensory assault. My first night there I couldn’t sleep with all the silence pressing in on me. I popped my new earbuds in and cranked up Depeche Mode’s Waiting for the Night . I fell asleep with the volume at level nine.

The next morning I woke at daybreak. Out of the darkness the sound of a violin bloomed. The rich timbre rolled through Amazing Grace. I blinked awake and softly sang along I once was lost, but now am found.

The whole month at the ashram was like that gentle wake-up call. Quiet support that was there if you needed it. We’d meditate, do hatha yoga, eat, train, meditate, eat, rest, and repeat. We were training not only how to teach a hatha yoga class, but how to live yoga.

Integral yoga traces its lineage through Master Sivananda and draws heavily on Vedic texts like the Bhagavad Gita. We were constantly practicing samatvam yoga uchyatte; equanimity is yoga, to become steady in the ever changing world. The trick is to inhabit a state of “dual consciousness” where I could enjoy being a human but also stay connected to my higher self.

Yoga did its work on me and by the end of the month it was a no brainer for me to take mantra initiation. For me this meant that I would take vows to follow the path of Integral Yoga in service of others. And that I would receive a personal mantra—and along with it a kind of spiritual jump start—that would guide me in meditation. Repeating the mantra both in meditation and throughout my day like a mental soundtrack is a branch of Integral Yoga called Japa. This conscious repetition of the mantra would help me remove my limitations and simply be me. The lovely swami who awoke me on the first day with her violin presided over the humble ceremony.

After my time at the ashram I came home with determination to use love to heal my life. But Orlando took a sharp turn deeper into his addiction. Within months he was either drunk or sick from being drunk. In desperation he tried to detox at home, which should have been done under medical supervision. Instead he had a grand mal seizure in our kitchen and ended up in the hospital.

After that I felt sure that he had hit bottom. But he refused to go to rehab and refused to quit drinking. He stopped working. Most nights he lost control of his bowels in bed. His linebacker physique turned into obesity. He had diabetes which became uncontrolled; his feet were a mess of open sores that wouldn’t heal. A rash covered his torso despite the ointment we slathered on.

As he sank, I sank into despair and rage. I began calling him a drunk, a liar, an asshole. I slammed doors. I meditated three times a day and held onto my mantra like a life raft. One night I chanted in bed when I couldn’t sleep; Orlando kept moaning and pushed his arm against me to make me stop.

One night he passed out on the living room floor and I couldn’t get him to bed. My impotent rage took over. I kicked his back. He was so drunk that he didn’t even respond. I am still ashamed.

I began to realize that if I didn’t die by an accident caused by his behavior that I would change into a person twisted by rage. I told him that I didn’t see a way forward for us anymore.

That night he put his hand across my throat. Around two o’clock I woke to him standing next to the bed. He was so drunk that one eye rolled while the other stared at me. I used to call it his crazy eye; it meant he was moments away from passing out. He reached out and put his hand across my throat. He was in the perfect position to choke me.

He did not squeeze. I lay still. Eventually both of his eyes came into focus on his hand. He seemed surprised to see it there. He pulled away and stumbled out of the bedroom.

I don’t know if he remembers that night. We never talked about it. But soon after he agreed to move out and to get a quick divorce so I wouldn’t be liable for his behavior. He admitted in open court to “extreme and repeated mental cruelty.” We shared a cab, a lawyer, and divided up our stuff. When the papers were all signed, we hugged in the lobby. Like he had that first day back in junior high he bent his head down to my ear.

He said “Maybe I should just become a monk.”

I wish he would have. I began rebuilding my life and kept meditating and repeating my mantra. But Orlando’s life eroded. That hug was the last time I ever held him. He went to rehab again but got kicked out of a halfway house for drinking. He was homeless for awhile. He slid sideways and within six years his addiction killed him. His death was ruled accidental.

I kept meditating and let the mantra give me a place to witness my suffering, judgement, and expectations. It also helps me feel that part of me that is more eternal; like a seed of my full potential that just needs uncovering. Swami Satchidananda always said to love just because it makes you feel good, without any expectation of getting something in return. I have a long way to go, but the mantra helps.

The winter following Orlando’s death I went to his grave for the first time. As the wind shuddered through the cemetery it carried the echo of our lives together. Maybe our relationship lives in my willingness to live love as a state of being. My body, my traumas, my transgressions, my joys keep revolving. But there is part of me that remains motionless within this ceaseless dance. I am both the storm and the still center. The mantra connects me to both.

I chanted the Om Shanthi peace chant for Orlando. The wind stopped and the mantra lay at my feet like an offering. I heard only silence. I felt only love.